Inverse Methods Notes

Notes based on Inverse Problems: Basics, Theory and Applications in Geophysics by Mathias Richter and Inverse Theory and Applications in Geophysics by Michael S. Zhdanov.

Table of Contents ---

01 - Examples of inverse problems, Fredholm and Volterra equations

import jax.numpy as np

from jax import grad, vmap

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Growth rates for things like bacterial colonies are governed by the initial value problem

\[w'(t) = u(t)w(t), \text{ } w(t_0) = w_0 > 0\]on the interval $t_0 \geq t \geq t_1$. For a given continuous function $u: [t_0, t_1]\to \mathcal{R}$, which is the growth rate of the problem, the equation has a unique continuously differentiable solution $w: [t_0, t_1]\to [0, \infty)$:

\[w(t) = w_0\exp(U(t)) \text{, } U(t) = \int_{t_0}^{t_1} u(s) ds.\]This means that the cause, which is the growth rate $u(t)$, implies an effect on the population size $w(t)$. We can describe this as a mapping $T: u\to w$ parameterized by $t_0, t_1, w_0$. The associated inverse problem is the construction of a function such that for a given $w(t)$, $T^{-1}(w) = u$. This can be solved explicitly:

\[w'(t) = u(t)w(t) \implies u(t) = \frac{d}{dt} \ln w(t).\]In practice though, we have only a finite amount of data, so the best we can do is approximate $u(t)$ (if we’re solving the direct problem) or $w(t)$ (if we’re solving the inverse problem).

For the direct problem this is not an issue. Taking $\hat{u}$ to be an approximator of $u$ such that

\[\max\{|u(t) - \hat{u}(t)|\}\leq \varepsilon, \varepsilon > 0,\]we can find that

\[\max\{|u(t) - \hat{u}(t)|\}\leq C\varepsilon.\]This means that up to a constant, variations can be mitigated by taking better measurements.

If we’re interested in solving the inverse problem, we can add a perturbation to the measured signal $w(t)$ such that

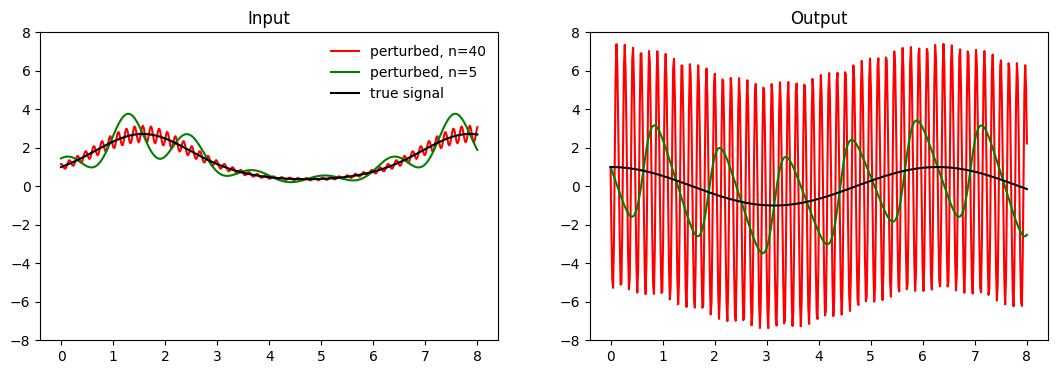

\[\hat{w}(t) = w_n(t) = w(t) * \left(1 + \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\cos(nt)\right)\]and we can see that $\hat{w}\to w$ as $n \to \infty$ which means that successively higher $n$ provide a better and better approximation for $w$. Now we can actually try to implement this in python.

w = lambda t: np.exp(np.sin(t)) # unperturbed signal

w_n = lambda t, n: w(t) * (1 + (1 / np.sqrt(n)) * np.cos(n*t)) # perturbed signal

The inverse of these functions are simply defined by the explicit inverse equation we found earlier: \(u(t) = \frac{d}{dt} \ln w(t).\)

def w_inverse(t):

ln_w = lambda t: np.log(w(t))

return vmap(grad(ln_w))(t)

def wn_inverse(t, n):

ln_w = lambda t: np.log(w_n(t, n))

return vmap(grad(ln_w))(t)

n_1 = 40 # first perturbation n, a fairly close approximation to the actual signal

n_2 = 5 # second perturbation n, a poor approximation of the signal

# grid of times to calculate

t = np.linspace(0, 8, 500)

We can see that as the perturbation is increased and the measurement more accurately reflects the signal, the calculated inverse function starts to diverge. In fact we can prove that despite the fact that this converges, mapping that to some inverse signal $u_n$ causes the inverse signal to diverge as $n\to \infty$.

This is because of the differentiation operation. Integrating acts to smooth out the signal, so it makes sense that its inverse, differentiation, would roughen it. This will blow up the perturbations in the input, which will make the explicit inverse equation almost useless in practice.

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(ncols=2, figsize=(13,4))

ax1.set_title('Input')

ax1.plot(t, w_n(t, n_1), c = 'r', alpha=1, label = f'perturbed, n={n_1}')

ax1.plot(t, w_n(t, n_2), c = 'green', alpha=1, label = f'perturbed, n={n_2}')

ax1.plot(t, w(t), c = 'k', label = f'true signal')

ax1.legend(framealpha=0)

ax1.set_ylim(-8,8)

ax2.set_title('Output')

ax2.plot(t, wn_inverse(t, n_1), c = 'r', alpha=1, label = f'perturbed, n={n_1}')

ax2.plot(t, wn_inverse(t, n_2), c = 'green', alpha=1, label = f'perturbed, n={n_2}')

ax2.plot(t, w_inverse(t), c = 'k')

ax2.set_ylim(-8,8)

Fredholm and Volterra Equations

Suppose we have some sort of integral equation which maps some cause to some effect, $u, w:[a,b]\to \mathcal{R}$, and has the form

\[\int_a^b k(s, t, u(t)) dt = w(s) \text{ , } a \leq s \leq b\]where $k:[a,b]^2\times \mathcal{R}\to \mathcal{R}$ is a kernel function. An equation of this form is called a Fredholm integral equation of the first kind. A special case of this is the linear Fredholm equation of the first kind, which has form

\[\int_a^b k(s,t) u(t) dt = w(s)\text{ , } a \leq s \leq b.\]If this kernel has the special property that $k(s,t) = 0$ when $t > s$, then the equation becomes a Volterra integral equation of the first kind, which can be written as

\[\int_a^s k(s,t) u(t)dt = w(s)\text{ , } a\leq s\leq b.\]Another special case is that in which the kernel function has the property $k(s,t) = k(s - t)$. In this case, the linear Fredholm equation is called a convolutional equation:

\[\int_a^b k(s-t)u(t) dt = w(s)\text{ , } a \leq s \leq b.\]Finally, we have Volterra or Fredholm equations of the second kind when the function $u(t)$ appears both inside and outside of the integral:

\[u(s) + \lambda\int_a^b k(s,t)u(t)dt = w(s)\text{ , }a \leq s \leq b\text{ , } \lambda\in\mathcal{R}.\]Linear Fredholm equations of the first and second kind have substantially different properties. Most notably, if the kernel $k$ is smooth (in the mathematical sense, e.g. continuous), then the mapping $u\to w$ also has that smoothing property. This means that a solution which involves inverting that mapping, which must necessarily invert an integration, must necessarily roughen $w$ and amplify the error. The computation of derivatives in the population growth example is equivalent to solving a Volterra integral equation:

\[u(t) = w'(t)\text{, }w(t_0) = 0 \iff w(t) = \int_{t_0}^t u(s) ds.\]Integral equations of the second kind contain unsmoothed versions outside of the integral, so they don’t necessarily have to roughen up in the inverse.

02 - Inverse gravimetry and full-waveform seismic inversions

Two of the “cannoncal” applications of inverse methods in geophysics are inverse gravimetry and full-waveform seismic inversions. In the former case, we might imagine that we’re trying to learn about the density profile of the Earth by looking at the force it exerts on an orbiting spacecraft such as GRACE.

Inverse Gravimetry —

Let the space that the Earth takes up be some subset $D\subset \mathcal{R}^3$, and let $S = \bar{D}$ be its closure. Then we can define a density profile for any point inside the surface of the Earth as $\rho : S\to \mathcal{R}$ with $\rho(x) \geq 0$. The gravitational potential of the Earth at any point in the space $\mathcal{R}^3\backslash S$ is defined by the convolutional equation

\[V(x) = -G \int_S \frac{\rho(y)}{||x-y||_2} dy = \int_S k(x - y) \rho(y) dy\text{ , where } k(x - y) = \frac{-G}{||x-y||_2}\]where we’ll assume that $S$ and $\rho(x)$ are well-enough defined that the function is Lebesgue integrable. The gravitational force exerted by the body occuping space $S$ is given by the negative gradient: $F(x) = -\nabla V(X)$. Obviously we can’t measure these values at every point in $\mathcal{R}^3\backslash S$ since that space has infinite measure.

Fortunately, we can imagine that the body of the Earth is contained by some convex space $\Omega$ (which may be a ball, for example, or half a ball, or whatever else) so that $S\subset \Omega\subset \mathcal{R}^3$. Then taking $\Gamma\subset\partial\Omega$, let’s say that we can measure the magnitude of the gravitational force on $\Gamma$. In practice, $\Gamma$ is going to be something like the track over which a satellite orbits, a lesser-dimensional subspace of the boundary $\partial\Omega$. We can express the magnitude of the potential function:

\[g : \Gamma \to \mathcal{R}\text{ , } x\to ||\nabla V(x)||_2\]This means that we can define a forward problem by the mapping $T : \rho \to g$ and $T(\rho) = g$. This means that we have an inverse problem which is $T^{-1}(g) = \rho$. This is a problem of inverting a convolutional equation. If we have appropriate $S$, $\Omega$, $\Gamma$, and $\rho$,

\[||\nabla V_1(x)||_2 = ||\nabla V_2(x)||_2 \forall x \in \mathcal{R}^3\backslash S \iff ||\nabla V_1(x)||_2 = ||\nabla V_2(x)||_2 \forall x \in \Gamma.\]Full-Waveform Seismic Inversions —

The idea of a full-waveform seismic inversion (FWI) is to obtain information about the Earth’s (or ocean’s, or star’s) structure from seismic waves generated at or near the surface. I’m going to use geophysical examples, but I believe the same ideas apply to astronomical examples (at least in principle). We can model the propagation of seismic waves in a domain $\Omega \subset \mathcal{R}^3$ by the elastic wave equation. A simplification of this which I will use exclusively is the acoustic wave equation, which allows us to ignore a lot of continuum mechanics.

The displacement at point $x\in\Omega$ and time $t \geq 0$ is given by the vector $u(x,t)\in\mathcal{R}^3$ which defines a vector field $u: \Omega\times[0,\infty) \to \mathcal{R}^3$. We can relate this to a deviation in equillibrium pressure by the equation

\[p = -\kappa\nabla\cdot u + S\]where $\kappa = \kappa(x)$ is the bulk modulus of the material and $S = S(x, t)$ is a source term. In geophysics this could be an explosive charge that triggers a seismic response or an airgun or hydrophone fired into the ocean for marine seismology. In white dwarf asteroseismology this would probably be a hydrogen or helium ionization.

Newton’s law tells us that these two terms are also related as

\[\nabla p = -\rho \frac{d^2 u}{dt^2}.\]We can see that knowing the domain $\Omega$, the density $\rho = \rho(x)$, and the bulk modulus $\kappa = \kappa(x)$ fully constrains the medium in the acoustic approximation. We can combine these two equations to get an expression for the propagation of an accoustic wave by noting that

\[p = \kappa\nabla\cdot u + S \implies \frac{d^2}{dt^2}\nabla\cdot u = \frac{1}{\kappa}\frac{d^2 S}{dt^2} + \frac{1}{\kappa}\frac{d^2 p}{dt^2}\] \[\nabla p = -\rho\frac{d^2 u}{dt^2} \implies \frac{d^2}{dt^2}\nabla\cdot u = -\nabla\cdot\left(\frac{1}{\rho}\nabla p\right)\]and the speed of sound in the medium is defined as $c = \sqrt{\kappa(x) / \rho(x)}$ so that $1/\kappa = 1/\rho c^2$, leaving us with a differential equation governing the propagation of an acoustic seismic wave in a medium:

\[\frac{1}{\rho c^2}\frac{d^2p}{dt^2} - \nabla\cdot\left(\frac{1}{\rho}\nabla p\right) = \frac{1}{\kappa}\frac{d^2 S}{dt^2}\]with initial conditions

\[p(x, 0) = 0\text{ , } \frac{dp}{dt}(x, 0) = 0\text{ , } x\in\Omega\]and boundary conditions

\[p(x, t) = 0\text{ , } x\in\partial\Omega\text{ , } t>0.\]We can prove that under the correct conditions, there exists a unique solution to this set of equations, meaning that there exists some mapping $F : (\rho, \kappa) \to p.$ Our hydrophones will only detect the pressure along some subset of the domain $M \subset \Omega \times [0,\infty)$, so our actual measurement will have an image which is the restriction of $p$ to the subset $M$:

\[T : (\rho, \kappa) \to p_{|M}\]Our inverse problem then is of course recovering $(\rho, \kappa)$ from an observation. As with inverse gravimetry, this is not necessarily a one-to-one mapping so there’s no guarantee that we can do this. We’ll need to make assumptions and simplify.